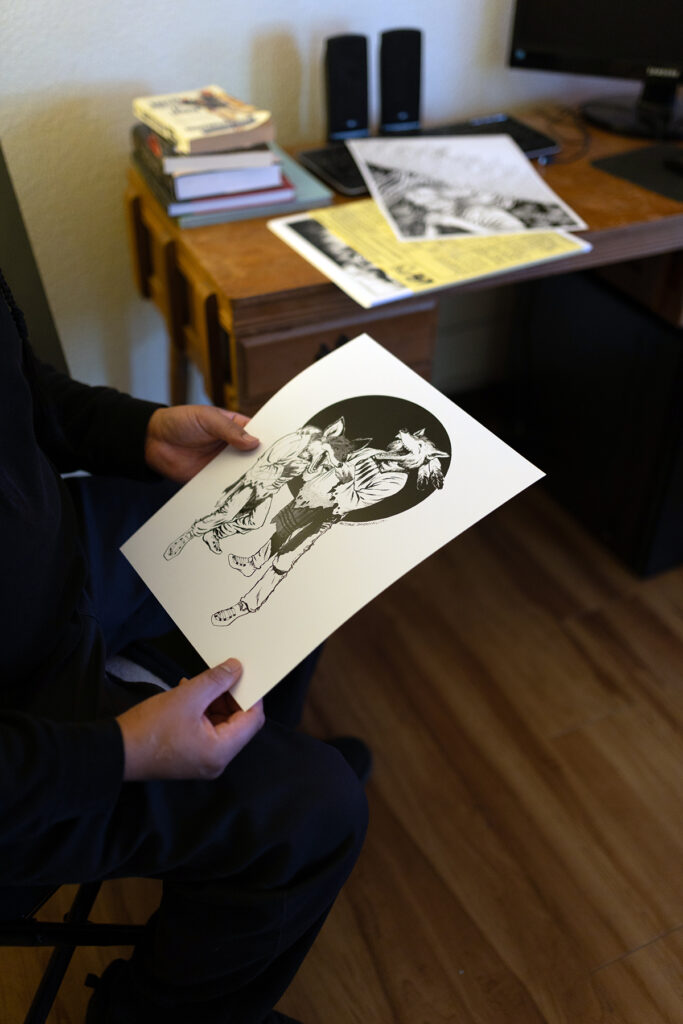

For about 25 years, Antoine, 45, has been the “go-to” artist for local businesses on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana. If people need new logos, signs, posters, or T-shirts, they come to Antoine.

“My dad was an artist. My mother, my brother, my sister, [too] – just an artistic family,” he said. “It would have been weird if I didn’t become an artist.”

Antoine has been able to rely on word of mouth to advertise his services. His name is on artwork all over his community. One of his paintings was used as a movie poster for a documentary about how bison first came to the Flathead Indian Reservation.

A father of five kids, Antoine is especially close to his youngest, an 8-year-old son. “I see him every day,” he said.” I talk to him every day. He’s a daddy’s boy.”

Last year, Antoine and his son became separated when Antoine was arrested for his second time driving under the influence. He was detained in jail for about a month on bail he couldn’t afford. His incarceration took a toll on everyone in the family, especially his son. A month seemed like forever. For the young boy, it was traumatic.

“Just being separated like that, you know, it’s terribly emotional, and not just emotional for [my son]. You know, it was emotional for me and everybody else who has to kind of deal with all that.”

After a month in jail, Antoine was put on probation, and he worked hard to follow all of the rules. He was highly motivated because if he violated probation, he’d likely have to go back to jail for an additional 210 days. He couldn’t imagine putting his family through that.

Antoine says he was sober for almost the entire year of probation. But alcohol use disorder is common in the United States – affecting more than 10% of Americans – and difficult to break. Most people relapse within their first year.

Antoine relapsed with just a few days left on his probation. “It only took one day to screw it all up,” he said. “A whole year down the drain.”

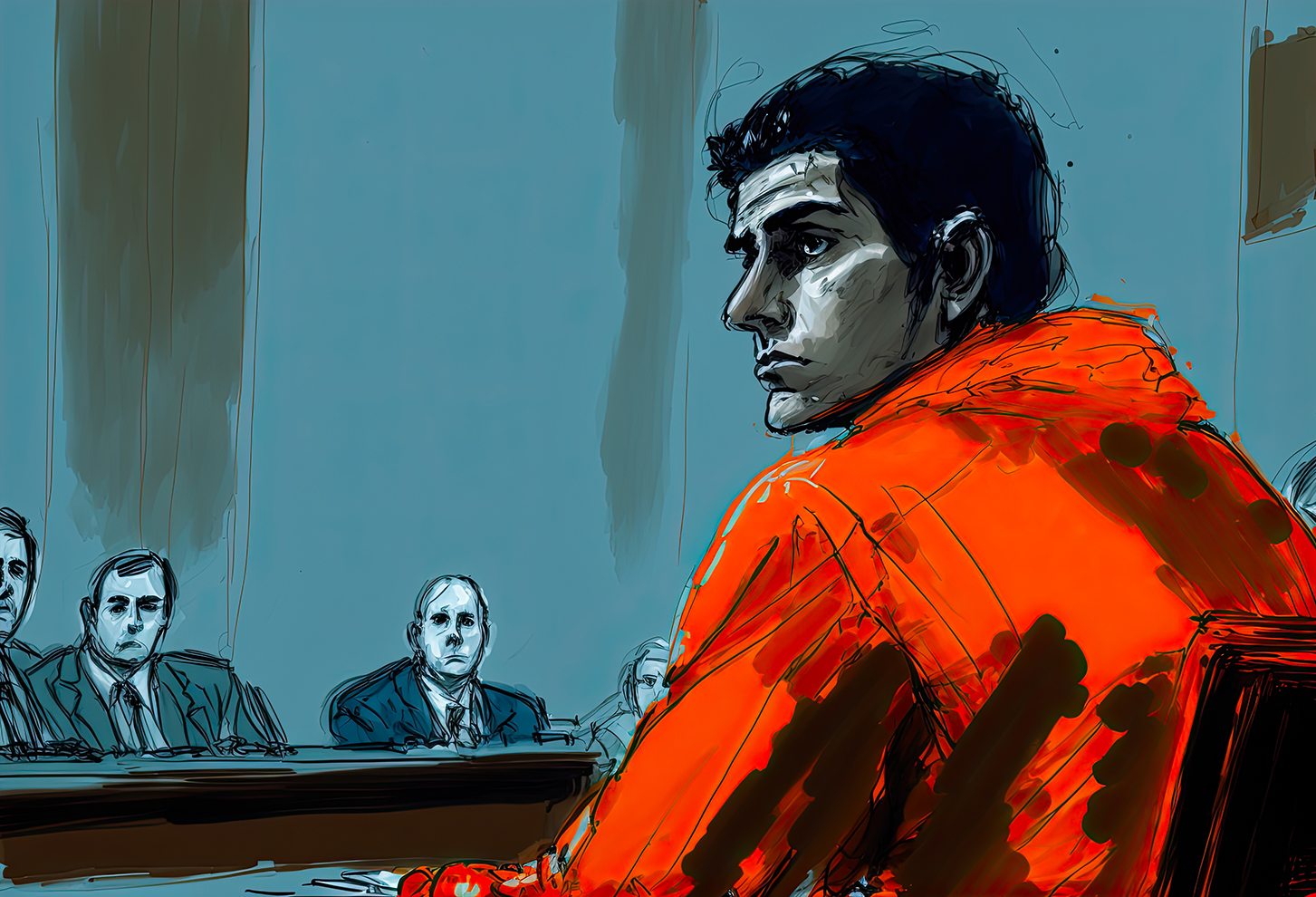

Antoine was charged with violating his probation and bail was set at $5,000, which he was again unable to afford. He had begun serving a sentence before he was convicted – simply because he didn’t have the cash. Once he was incarcerated, Antoine’s family, including his young son, lost contact with him again.

While detained, Anoine anticipated the worst. When he was initially placed on probation, he had been warned that any violation would mean that he’d have to spend 210 days in jail, so he prepared to spend that time in jail away from his family.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. Almost 70% percent of people in local jails have not been convicted or sentenced, but are in jail because they can’t pay bail. The incarcerated population has nearly quadrupled since the 1980s, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. This two-tiered system of justice, where those with money to pay bail are released, and those without money stay in jail, means that those who cannot afford bail are serving a sentence before even being convicted of a crime.

“All of these people just can’t afford to be out,” Antoine said, reflecting on the people he saw alongside him in jail.

Most Americans would be unable to pay a $5,000 bail, like Antoine. The majority (57%) of Americans cannot afford an unexpected $1,000 expense, according to a recent study by Bankrate. For people living in poverty, finding $5,000, let alone $500, can be impossible. “There are a lot of people who I spent time in jail with who couldn’t even get out with a $100 bail,” Antoine said. “They just can’t.”

Like Antoine, many people fall into despair as they wait for the resolution of their case from behind bars. Hopeless, some plead guilty to crimes they believe they are innocent of, just so they can go home: the pressure to resolve their case and escape jail is that great.

For Antoine, his sadness was unrelenting. He missed his family. Then one day, he heard that The Bail Project had paid his bail at no cost to him. He was going home.

“It was literally out of the blue,” he said. “It felt like a miracle.”

Because his case was still pending, his release on bail was potentially temporary. If found guilty or convicted of the probation violation, a judge would determine whether he’d be required to serve additional jail time or not.

At home, while waiting for his case to be heard, Antoine could help his family prepare for his potential incarceration. To make sure his children would be provided for if he went away, he took on as much work as possible. He was also able to get ahead on his rent, so that he wouldn’t lose housing while incarcerated. Most importantly to him, Antoine was also able to explain to his son what was happening and assure him that things would be alright until he came back.

Some people argue that without money on the line, people may not return to appear in court or to serve out an eventual sentence if they are found guilty. However, the idea that people flee from court is not borne out by the evidence. Most people, because of family and other obligations like their jobs, are tied to a place and have no desire to leave. People also return to court because they want to take accountability or because they want to prove their innocence. In the rare instance that someone doesn’t appear, it’s usually for the same reasons that most miss dentist’s appointments: they couldn’t get time off from work or arrange childcare; they got stuck in traffic; or couldn’t access reliable transportation. People living in poverty also experience chronic scarcity, where they are forced to spend most of their time navigating competing basic needs. For them, other matters that may not be as vital or immediate, such as a court appointment, can easily be forgotten.

Antoine had no issues returning to his court dates. He made every single one, even with none of his own money on the line, and with knowledge also that at the end, he might be sent back to jail. Most of The Bail Project’s nearly 30,000 clients are just like Antoine – and have returned to court 91% of the time.

Antoine said money wasn’t necessary to get him to come back. He understood that attending to his case and being present in court was the only real option.

“If you don’t [go to court], it’s only going to get worse,” Antoine said. “Just facing the music is better.”

Beyond just having additional time to spend with family, there are many advantages to releasing someone while they wait for their case to be heard. People who are released while their cases are pending have measurably better court outcomes than people who are forced to remain in custody while they fight their case. They are less likely to plead guilty and be convicted. They are also less likely to serve jail time if they’re convicted.

Because Antoine had done so well on probation, the sentence for his violation was reduced to 54 days. He only served half of that time in jail; The Bail Project helped arrange for him to spend the other half in a treatment program, which he says was far more helpful at addressing the underlying issue of his alcohol misuse.

“In jail, you are not learning anything … about coping or dealing with addiction,” he said. “You are just sitting, watching TV, and waiting for meals.”

In recovery, he learned strategies to keep his alcohol cravings at bay. Unlike in jail, he was able to access his art supplies, which have been critical tools in his recovery.

“My experience with The Bail Project has been absolutely phenomenal,” he said.

Thank you for reading. The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you. If you found value in this article, please consider supporting our work today.